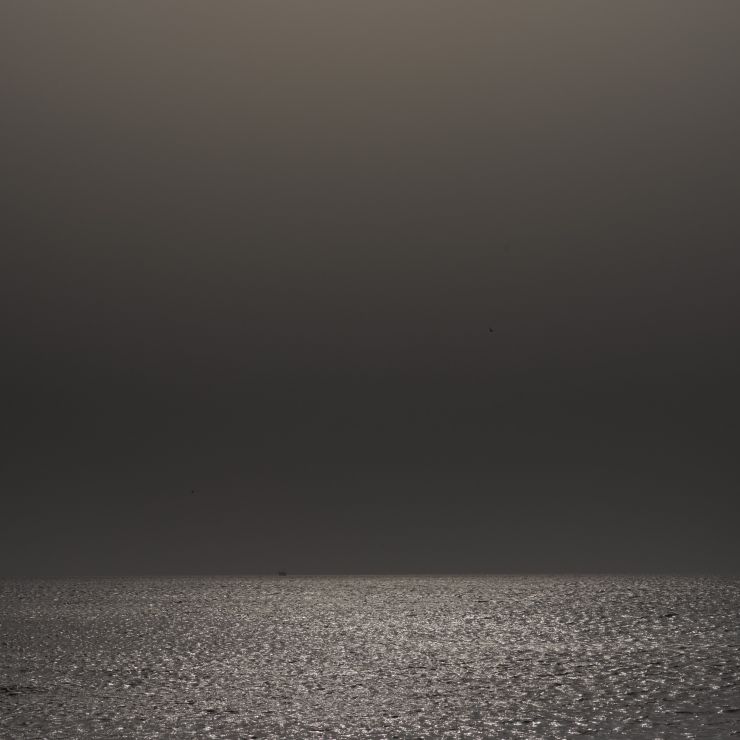

The Bermondsey Project Space collaborated with the Good Governance Institute to exhibit Tim Nathan's photography during the Festival of Governance. The exhibition ran from August 31 to September 4, 2021, showcasing Nathan's seascape photography, which reflects his personal journey through mental health struggles and resilience. His work is influenced by his love of horses and drawing, and he continues to innovate across various creative fields.

The exhibition represents an opportunity to collaborate with people and organisations who share our values and ambitions. Participation and imagination, original thinking and the sharing of ideas are as fundamental to the ethos of Bermondsey Project Space as they are to the Festival of Governance, an important event we are proud to be part of.

So what led Tim to produce this stunning series of seascape photographs, a creative process that represents a departure from his normal artistic concerns? …

and why have they resonated so deeply with those who find themselves confronted by them now?

It would be easy to fall back onto a more formal Art Historical approach to investigate these questions. I could make equivalences and comparisons with the romantic paintings of Caspar David Friedrich - indeed when I imagine Tim alone on the beach at daybreak underneath gigantic winter storm clouds, Friedrich’s depictions of the lone figure set against the huge scale and power of nature do come to mind. It would be just as predictable to refer to the foreboding and brooding seascapes of Emil Nolde. Instead, I want to go beyond the obvious and focus on a more biographical angle that considers how these photographs bear testament to the photographer’s struggle with mental health issues. More than that, I want to discuss how Tim led himself out of his mental health crisis by radically changing the narrative of his life.

The pandemic and its consequent lockdown requirements have caused each and every one of us to deepen our level of reflectiveness.

It has forced us to readjust our priorities. Irrespective of all the hardships and challenges it has brought, it has also seen many of us grow, develop, and begin to think more profoundly. Whilst Tim is adamant that lockdown did not directly cause his mental health crisis - he claims that he found the restrictions strangely liberating - I do think that it provided the conditions for his existential breakdown.

2020 was a tough year for Tim. Sadly his father died and tragically he was unable to attend his funeral because of lockdown restrictions. In his last decade, he has endured chronic and acute anxiety and depression. In his own words he “deals with this on a daily basis”. Dogged by the perpetual feeling that he is never living in the present he tells me that his depression is always coupled with intense feelings of disassociation. He explains that he also experienced overwhelming sensations of boredom and annoyance because despite understanding his condition, such self-knowledge brings him no relief.

Tim began to suffer attacks on a daily basis that left him lying on his studio floor in helpless tears. He began to feel huge disappointment in himself, explaining later “I had worked so hard on myself, been in therapy, adopted a regime of self-care and now I felt like I had failed” His sense of self-worth nosedived and knowing himself so well, he became aware that it was going to take a huge effort and considerable time to pull himself out of the hole he had fallen into. Worryingly he wasn’t sure whether he had enough reserves to succeed. He says he knew he just had to throw himself into his work. Additionally, he tells me that he decided to “change everything I do”. He overhauled his diet, started a daily routine of yoga, stopped drinking, and began walking incessantly.

These photographs are not the result of any grand preconceived project. They started with Tim impulsively deciding to take his camera on one of his now routine walks along the nearby shoreline of St Leonards-on-Sea.

an additional way of radically redefining who he was. Tim started to post his seascape photographs with neither commentary nor comment on social media. Early feedback showed that the work was beginning to touch people profoundly. This, he says, gave purpose to his daily photographic excursions and enabled him to enjoy some validation for the work.

When I commented to Tim that he often braved inclement weather to capture some of the more dramatic seascape photographs, he remarked that ‘There is no such thing as bad weather, just bad clothes'. It occurs to me that just as you need to change your clothes to weather a literal storm, a sudden downturn in mental health requires a change in mindset to one that is more protective and generative as much as possible.

That is exactly what Tim did.

Some argue that the causes of suffering are disproportionately inside of us,

not in the ‘out there’ world of political or economic systems that shape how we live - that if we meditate or practise mindfulness then we can still flourish even though we may be under huge external pressures. Others argue that this view can take away from our motivation to act pragmatically and to initiate positive changes in our external world. Of course we need to look after ourselves and serve other people and causes … it is not either or.

These series of photographs are a manifestation of self-leadership. Tim realized he needed to break away from old habits, to change the very things that he did every day in order to battle his black dog. By flipping his script, he carefully governed himself out from his despair. Through his fortitude and willingness to adopt a different mentality, he has shown us the importance of self-leadership. He poses the question: How can we be expected to lead others and to have any positive impact in the world if we cannot lead ourselves mindfully?

To me these photographs are about coming to terms with impermanence. The sea is never the same two days running. It literally ebbs and flows - changed by tides, wind and fluctuating light. Similarly, scudding clouds flow from horizon to horizon, and are never the same twice. Buddhism tells us we need to lean into the idea of impermanence in order to lessen our suffering. In the same way that Tim’s seascape photographs distil the ever changing and fleeting nature of reality, they also speak to the idea that our emotional and mental landscapes are not permanent and are not who we are in essence. We can change them and lead ourselves out of the storm clouds if we can develop resilience and harness effective strategies.

One reason why these photographs have engaged so many people is because they provide points of communion. When we look at them we share Tim’s hardship and gain some relief in knowing that we have all faced challenges during the pandemic. For that reason I would like to dedicate this to all those who, by whatever cause, have found themselves close to the brink in the last year or so.

All power to you!

Gareth Stevens